In a world where almost half of the global workforce (46%) is self-employed, as estimated by the ILO in 2023, the importance of setting a pay floor for these workers to live decently must be emphasised.

A few weeks after the ILO agreed to develop global standards on decent work in the platform economy, WageIndicator was pleased to spark the discussion on pay floors for the self-employed at the 2025 Regulating for Decent Work Conference in Geneva, during the session “Living Wages, Dignity and Decent Work in a Transforming Global Economy.” Chaired by Paulien Osse, Co-founder and Head of the WageIndicator Living Wage Team, the session focused on fair compensation as a pillar of decent work.

The session also provided an opportunity to present the Living Tariff methodology, which is based on WageIndicator Living Wage calculations and helps freelancers and gig workers calculate sustainable rates more accurately. Some preliminary empirical insights were presented.

Following his return from the conference, we talked with Martijn Arets, a global platform expert who presented the paper he wrote together with Marta Kahancová (CELSI) and Paulien Osse: "Living Tariff: The Case for Setting an Income-floor for Self-employed in the Gig Economy and Beyond". We collect his impressions and get some insights from the event.

Daniela Ceccon, the WageIndicator Data Director, joined us to explain how the Living Tariff is calculated and how it is connected with the Living Wages.

Pay floors for the self-employed: do we care?

Dani, Martijn: thanks for being here today. Let's start with you, Martijn. WageIndicator has been talking about the Living Tariff ever since when it was first introduced at the end of 2023. But what did you focus on in Geneva?

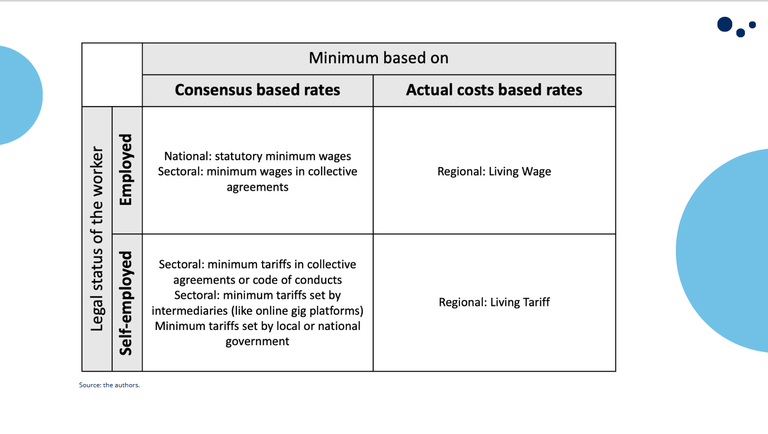

I started my presentation by noting that, based on ILO figures, 46% of the world's working population is self-employed and that, except for a few exemplary local and mostly sector-dependent examples, there are no pay-floors for this group. And continued with the question: should we care about 46% of the world's working population? This simple no-brainer message paved the way for the Living Tariff methodology.

In my presentation, I also deliberately separated the methodology of a cost-of-living based approach from the interpretation of how WageIndicator implemented it. It is important to first reach consensus on the fact that the methodology, which builds on the Living Wage methodology, is needed. To then talk about the interpretation.

And what was the audience's response to this?

I made it clear that it is a responsibility for all stakeholders to engage in this debate, and the reactions afterwards to this were very positive, although I realise that this is a long-term process.

I made it clear that it is the responsibility of all stakeholders to engage and that setting pay floors is a long-term process. However, the reactions afterwards were very positive, reflecting the comments we received from other experts who agree that the Living Tariff could represent a breakthrough, even in the Global South.

The fact that the ILO is now working on a Platform Work Convention ensures that the momentum for this discussion is perfect, as it also discusses pay and living wages.

Pay floors for the self-employed: behind the Living Tariff

Dani: Before we move on, let's clarify some basics for everyone to set the scene. What components must be taken into account when calculating the Living Tariff, and in what ways is it different from the Living Wage?

Absolutely! The Living Tariff builds directly on the components of our Living Wage (like food, housing, transport, clothing, healthcare, and education) but it goes a step further to reflect the realities of self-employment.

While the Living Wage assumes an employee working regular hours with some employment protections, the Living Tariff includes additional social protections for self-employed and, depending on the job, also occupational costs and coverage of the time spent on activities that are needed, but are not part of the work. For the occupational costs, think of tools of the trade, like a laptop for a freelance translator, a bike for a rider, or a car and petrol for a taxi driver. As to social protections, since freelancers don’t have an employer to pay into social security, we include both employer and employee contributions for things like health insurance and pensions.

And what about time?

Depending on the occupation, we also include time not spent earning, covering hours spent on activities like administration, training, or waiting between gigs. All essential parts of freelance work that aren’t directly paid but still take up time.

So the starting idea behind the Living Wage and the Living Tariff is the same, but it has been adapted.

Exactly. While both concepts start from the same assumption - that everyone deserves a decent standard of living - the Living Tariff adapts it to the needs of freelancers and gig workers by accounting for the extra risks and costs they face.

Living Tariff: The Hidden Costs of Being Self-Employed

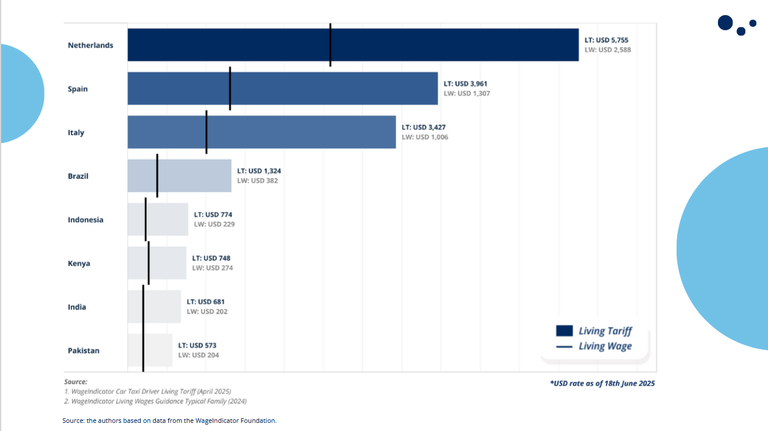

Martijn, during your presentation in Geneva, you compared the Living Tariff and Living Wages in a number of countries, and the empirical insights were noteworthy.

The empirical insights revealed various key takeaways:

- Firstly, the Living Tariff is always higher than the Living Wage. And Dani can tell you more about that.

- Secondly, one universal Living Tariff is not sufficient: This is why we provide a basic rate for freelancers and we then differentiate by occupation.

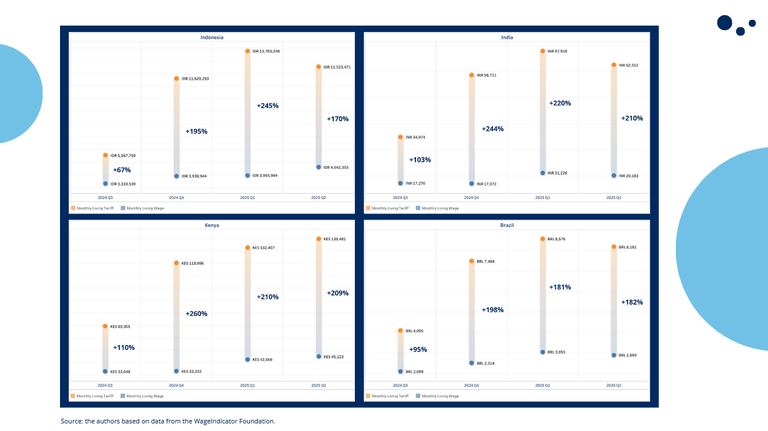

- Finally, the Living Tariff is based on cost-of-living data. We receive new data on a quarterly basis and must adjust the Living Tariff accordingly.

These insights may not be surprising to someone who is already familiar with Living Wages, but visualising them based on data makes them very tangible.

It was also particularly cool to see how knowledge from all corners of the WageIndicator Foundation comes together; I really see that as something unique.

Dani, for the majority of the analysed countries in another set of empirical insights (see the image below), the Living Tariff is often double or triple the amount of the Living Wage, as Martijn mentioned. Could you provide us with more details on this?

Yes, that’s correct, and it’s actually one of the most eye-opening findings. While the Living Wage covers basic living costs for employees, the Living Tariff reflects the real earnings a self-employed worker needs just to break even. Once we start including work-related expenses, the gap becomes clear.

What more can you tell us about calculating work-related costs?

They vary a lot by occupation, and the insights shared in the presentation combine the occupations.

- For example, a motorcycle courier needs to cover the cost of the bike, petrol, maintenance, a helmet, insurance, plus a phone with access to data.

- An online worker needs a laptop and a good wi-fi connection.

- A taxi driver has to pay for car repayments, fuel and a mobile phone with data.

Starting with that, we include social contributions (both employee and employer parts) and time for admin, training, and job-searching, because these are real parts of the job for freelancers and gig workers.

When you put all of this together, it’s easy to see why the required tariff per hour can be two or three times higher than the equivalent Living Wage.

Martijn, steps that still need to be taken include reaching a consensus on which general components and occupation-specific elements should be included in the calculation, and how these variables should be calculated and interpreted. What would you like to add about this?

Like a Living wage, a Living Tariff is almost never legally enforceable - even though Collective Agreements could be used for this purpose. This makes it essential that all stakeholders in the debate are involved in the reasoning and necessity. Only when everyone understands its importance can the right steps be taken.

I think the Living Tariff can benefit from the current attention for decent platform work, because ultimately it is about the (political) will to change something. I believe that starting small and learning and experimenting is the best way to begin.

Is WageIndicator already having talks?

Yes, we are talking to various initiatives about how the Living Tariff can be incorporated into a code of conduct, for example. Some multinationals are already using Living Tariff estimates to plan for their self-employed associates, or 'consultants', as they call them.

Although the idea of the Living Tariff and the first steps towards its realisation come from the WageIndicator Foundation, the methodology of a cost-of-living-based pay floor for self-employed workers must be quickly embraced by everyone and a sense of ownership built up. These kinds of methodologies can only take off when you let them go.

In your presentation, you conclude that 'pay floors do not operate in a societal vacuum'. What did you mean by this?

This is something I learned from my experience in the debate around platform work. When you regulate something for a certain group of self-employed workers, you have to look at the entire market and address the conditions there. In platform work, for example, there are often calls to improve the situation of workers who work via platforms, but the fact that the rest of the market is informal and precarious is forgotten (read: ignored). That in itself is painful, of course, because many stakeholders in the debate have ignored less regulated sectors for years. But the only way to do it right is to tackle an entire sector at once.

Next steps: navigating legal voids and finding scalable solutions

Martijn, Dani, let’s wrap it up. What are your teams going to do in the next few months to make the most of this inspiring research?

Martijn: To start with, we need to finish and submit our paper, so that there is a solid academic foundation for this methodology.

In addition, I would like to divide the steps we are going to take into “front end” and “back end”.

In the front end, we will engage in dialogue with many stakeholders about the methodology. Here, we will provide information and gather information and feedback. As a central hub, we want to connect stakeholders and facilitate the debate. We will also work with different groups to validate a Living Tariff for specific target groups, again to gather input.

The Living Tariff is a complex methodology, because it contains variables that will always be open to discussion. But ultimately, we want it to have an impact on workers: a methodology for the sake of a methodology is pointless.

In addition, we will work on the back end to improve the way we implement the methodology Dani, I'll leave it to you on this point.

Dani: Yes, we definitely see a lot of potential for the Living Tariff and would love to expand the tool to more countries. We already calculate Living Wages in 178 countries, so the data foundation is there, we just need to add the specific occupational layers.

One key focus going forward is improving the quality of data on work-related costs. We want to better understand which tools, equipment, and other expenses are really essential in different jobs. For example, we don’t yet have enough detailed information about the costs cleaners face, like supplies, uniforms, or transport, and that’s something we’d really like to include. We are also exploring ways to improve the estimation of waiting times

So the next steps are both scaling and deepening: bringing the tool to more countries, and making it even more relevant and accurate for different types of freelance and gig work.

Related content

Find out more about pay-related issues affecting gig workers and freelancers:

Living Tariff and gig workers: a new concept for calculating costs and raising awareness

Towards a Living Tariff: Even freelancers deserve a fair income